Sometimes a life story doesn’t turn out as you expect. You want it to be an ending of happily ever after even if they have endured some tragedy or mishaps along the way. Part of researching a family member is finding stories that are tragic, overrun with sadness and even grossly unfair.

I started researching my 1st cousin 3x removed, Leslie Prothero. It intrigued me that he had left his large family in Young, NSW to live in Toowoomba. The majority of his brothers and sisters and more than 40 cousins were still in the town. As the facts of his life revealed themselves, I was intrigued, saddened and shocked at its ending. I wrote the story for the Toowoomba & Darling Downs Family History Association and it is included in their publication Our Backyard & Beyond Volume 6.

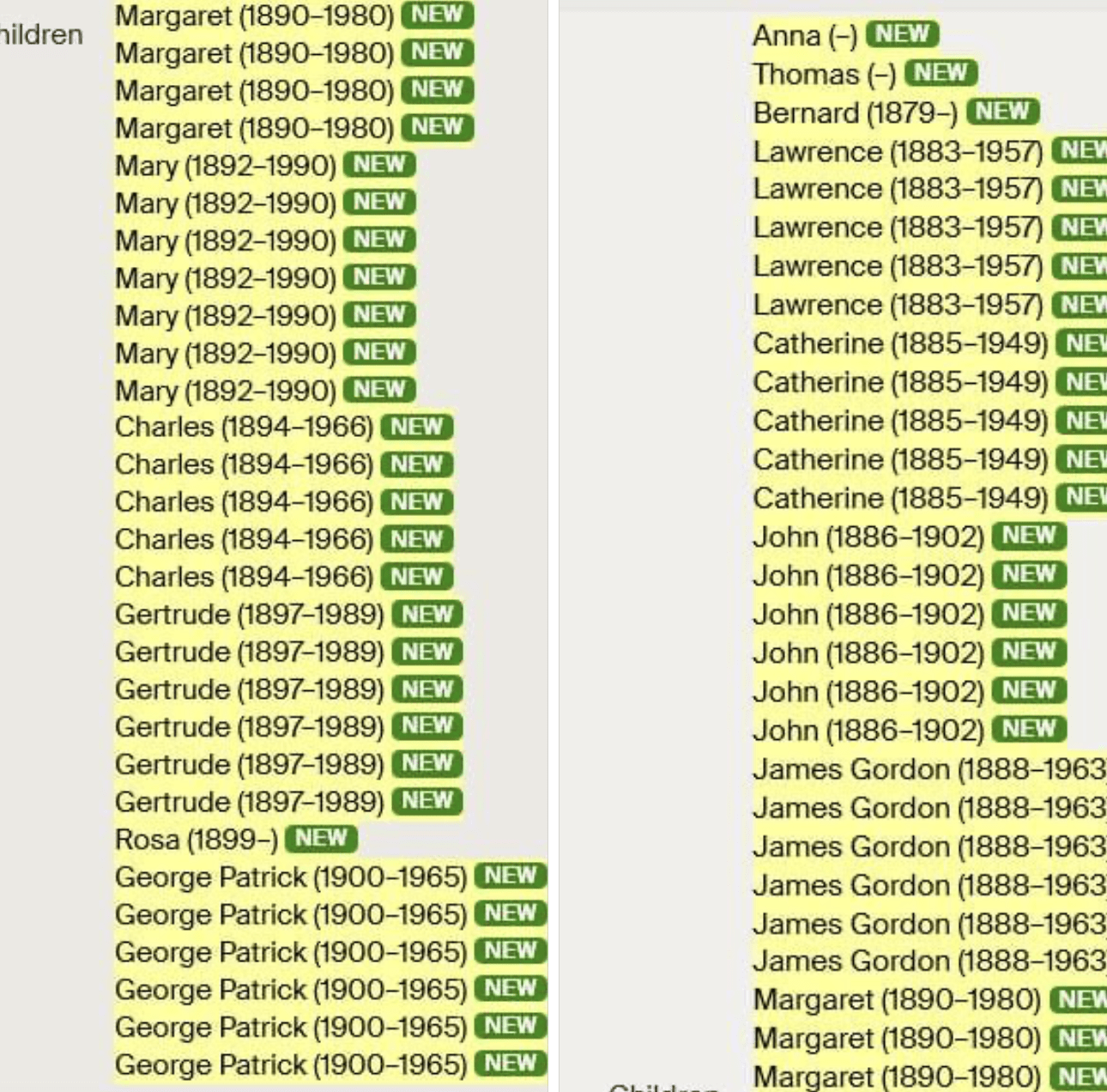

Leslie Prothero is born on 2 April 1895 in Young, New South Wales, ninth of ten children of Frederick and Bridget Prothero. He spent his childhhod with six brothers, three sisters and over 40 cousins. His mother, Bridget Fox is born on the gold fields at Burrangong in 1861 to Irish orphan Margaret Wogan and Irish convict William Fox. Bridget is part of a large family with seven siblings from Margaret’s three relationships. In 1879, at the age of 18, Bridget is married to Frederick Prothero. He is a respectable husband, born in England and working as a bookkeeper.

In 1913, when Leslie is 18, his father Frederick dies at age 59. War is declared the next year, and Leslie follows four of his brothers to Sydney. He enlists on 29 January 1915. It is not long, however, before he is called back to Young, wanted for deserting a child he has fathered with Catherine Gregory. She names Leslie as the father of her daughter Mavis. Leslie is arrested by Sydney police in May 1915 and charged with failing to make provision for the payment of preliminary expenses of an infant. He is remanded to Young where he pays what is required and is discharged, free to return to training camp in Sydney.

On 25 June 1915, Leslie boards the ship Ceramic and embarks for England. On arrival they are transported to Gallipoli, arriving there on 5 August. With barely a moment to put down their packs and meet their battalion mates, they are thrown into a battle now known as Lone Pine. Leslie’s battalion mate, Harry Clarke reminisced in The Blue Mountain Echo published on Fri 1 Aug 1924 about the Lone Pine charge:

I can never forget the absolutely unaffected nonchalance of those original Anzacs of whom we were now a part. We were ordered to stow our packs into a big cavity of one of the trenches exalted by the name of quartermaster’s store. The silence, the calm serenity was portentous. We were overlooked by the Turks’ trenches, yet not a shot was fired from either side; it was like the silence of the bush insects which immediately precedes a storm. By orders, which, seemingly, came from nowhere and from nobody in particular, we gradually crawled into cover of the dugouts and under shelving rocks. I found myself on the outer entrance of one of the latter, one of a huddled-up group of fifteen. Strangely enough, nearly every one of us were cobbers who had been together right through the camp at Liverpool and had left Woolloomooloo in the same boat – the Ceramic.

The air was suddenly filled with spiteful, screeching, hissing shells of all sizes. In front of our shelter the shrapnel fell, spurting up the earth and gravel. The overhead shrieking of the shellfire was demoniacal, beneath us, the solid rock and earth literally shook. Next came our turn to hop out; run forward a few yards; drop down, rush forward again and so on, until those of us who survived reached the temporary shelter of the sap. The exit from this sap opened on to no-man’s-land, immediately fronting the Turks’ trenches. It was strewn with killed and wounded. On the top of the trenches could be seen our boys ripping up the coverings to make gaps through which they could drop into the trenches, not knowing whether they would alight among friend or foe. It was mad, blood-curdling pandemonium; hell let loose. The parapets and the bottom of the trenches were littered with killed and wounded. Worst of all were the shrieks of agony, the curses of the frantic, the groans of the dying and the pitiable appeals from the pain stricken wounded.

Writing to his mother, Leslie talks of his experience during the Lone Pine campaign:

“I went through some very heavy fighting while I was over at the Dardanelles, and so did Bill. I was in three charges and never got hit. I consider myself very lucky. We have lost very heavy, our last charge cost us 2000 men, dead lying everywhere. Our boys stop at nothing. When you see your mates falling it makes your blood boil, and in a charge, you go mad, and when it is over you hardly know what you did. Fine sport when you get them on the run and us after them with the bayonet.”

A few weeks after the Lone Pine battle, on 16 September, Leslie shows symptoms of dysentery and is evacuated from Gallipoli to the island of Mudros. The conditions in Gallipoli are filthy. Masses of flies carry disease from rotting corpses to the water and food consumed by the troops. The symptoms of dysentery, including bloody diarrhoea, cramps, pain, and fever, sap the strength from the men who are already weak from a lack of quality food. Leslie’s condition doesn’t improve in the hospital on Mudros so he is transferred to England, leaving on 21 October on the HS Aquitania. He remains in England until May 1916, when he re-joins the 1st Battalion in France.

Back in Young, his mother Bridget is a regular in the newspaper. The headlines include, “A fighting family. Five sons on service.” Bridget is “the proud mother of five sons who are doing service for the Empire.” The Young Witness newspaper publishes stories and letters throughout the war of the experiences of Leslie and his brothers, John, Fred, Thomas, and William.

In 1917 Leslie suffers several bouts of trench fever, an infection spread by lice with symptoms of a rash, headaches, fever and often a severe pain in the back and shins. On 4 October, Leslie is back with his battalion and is shot in the foot, and again evacuated to England to recover. In England, in May 1918, Leslie hears of the death of his brother William at Villers Brettoneux during the battle of Hangard Wood. Leslie does not go back to the front for the rest of the war. He is assigned to the Army school of instruction and then the Survey School in Southhampton. Here he meets 20-year-old Sadie Owens from Liverpool. On 5 April 1919, they marry and on 3 July embark for Australia on the Zealandic with their three-week-old daughter Doris. They arrive in Sydney on 23 August and Leslie is officially discharged from the AIF in October 1919.

During the 1920’s Leslie works for NSW Railways and in Katoomba on the conservation dam. He trains and qualifies as a fitter and turner. In 1921 Sadie gives birth to their second daughter Mavis. By 1930 they are living in Sydney in Trafalgar Street, Annandale in a historic Victorian home transformed into three flats which is one of many homes where they reside. Only a few years later in 1933 their marriage has ended. Sadie is living alone in Lilyfield and Leslie is in Artarmon.

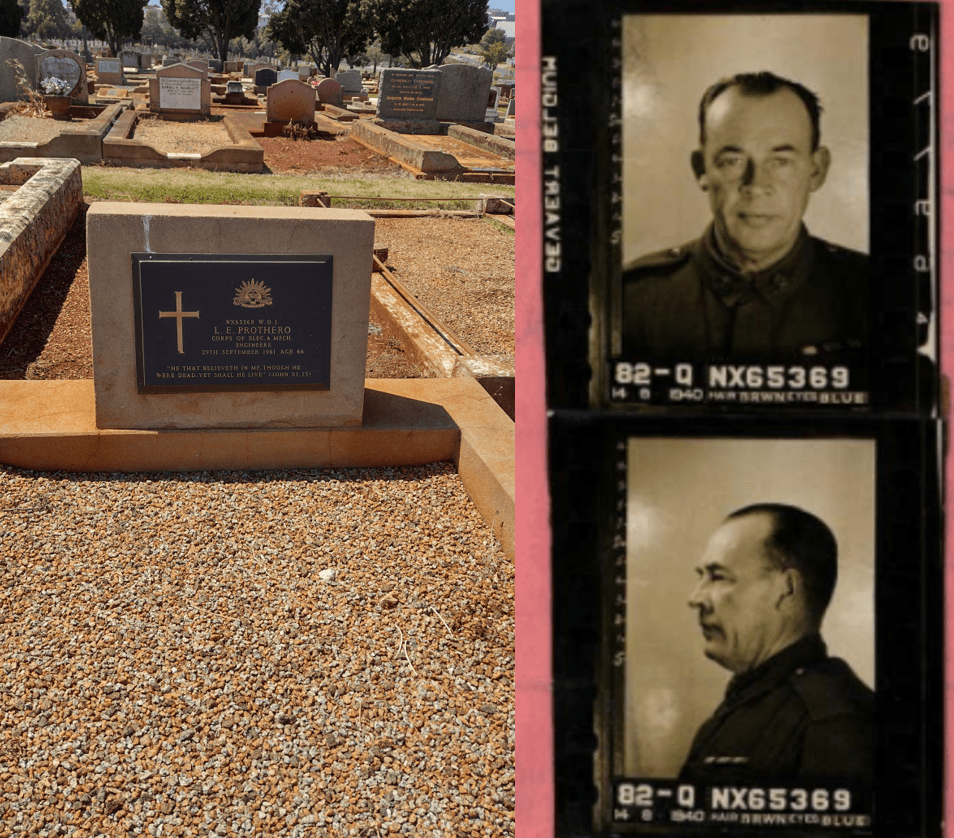

The state of their marriage becomes clear in 1939 when Leslie enlists for service in the AIF on 12 October in North Sydney. He lists Sadie as his wife but her address as unknown. His attestation papers record his date of birth as 2 April 1900, cutting five years from his age and bringing him under the age of 40 so he is able to enlist. After a year’s service in Sydney with the 2nd Battalion, Leslie embarks for Egypt on the 27 December 1941. During his service in Egypt and the Suez Canal the area was under constant threat by the Germans. The only thing stopping the capture of the canal are the Rats of Tobruk who hold onto the garrison of Tobruk despite constant bombardment between April and December 1941. During his service in Egypt, on 27 November 1941, Leslie’s eldest daughter Doris Prothero dies in Balmain Hospital. She is 22.

Leslie leaves Egypt on 4 February 1942, returning to Australia and serves in battalions in Sydney including the Infantry Transport Workshop. He is hospitalised in April 1944 with eczema on his neck and hands. In July his records are updated with a new next of kin – Phyllis Telford of the Criterion Hotel, Drayton. She is listed as his friend.

On 1 June 1945 their daughter Phyllis is born and they set up home in Toowoomba. Tragically, baby Phyllis dies when she is only ten months old. Leslie and Phyllis have three more children, Patrick James Leslie Prothero in 1947, Brega Jill Prothero in 1948 and John Geoffrey Prothero in January 1952. Phyllis suffers terrible headaches after John’s birth so the neighbour steps in to help look after him. Ten months after John is born, Phyllis dies in Toowoomba hospital from malignant hypertension. Leslie is 57 when his wife dies and he is now the sole carer of Patrick, five and Brega, four. John is cared for by the neighbour.

Leslie is unable to look after the children, they live in orphanages and also board with Lillian Lindgren and her family in King Street, Toowoomba. Nine years later Leslie dies from emphysema and bronchitis, both of which he suffered for many years and resulted in the loss of one lung. He is 66 years old. Brega continues to live with the Lindgrens and Pat goes to live with the Bergin family in Brisbane. John is adopted by the neighbour and his name changed to Meisenhelter. He is unaware of his parentage until he is contacted by his sister Brega when he is in his 50’s.

Leslie is buried in Toowoomba and Drayton Cemetery, Roman Catholic Section 7, Block 7, Plot 48. Phyllis is buried next to her baby daughter in the Church of England Section 7. Both graves are unmarked.