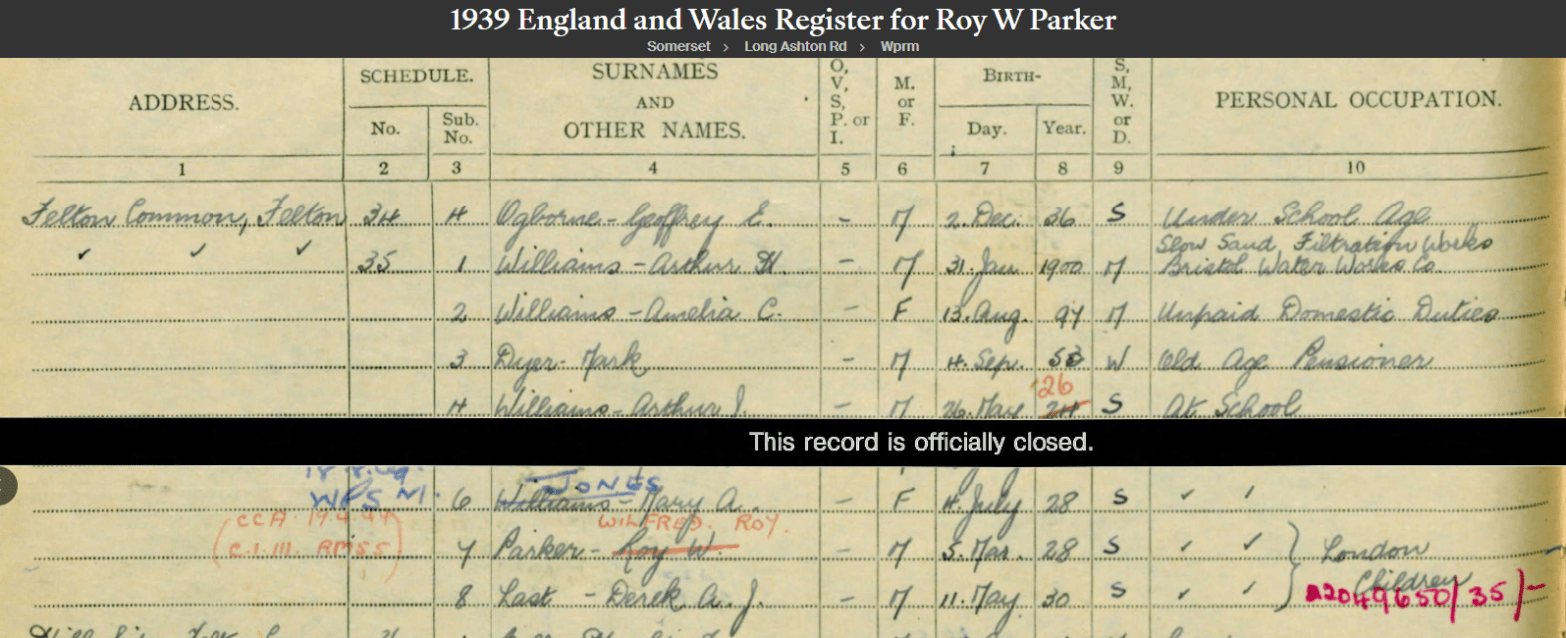

When records are searched and family trees are built, there can still be doubts about whether the person and family found is correct. A family tree is constructed by available records and often anecdotal evidence from descendants who are told about their family and where they came from.

Records rely on the informant to provide the correct information to the authorities and there are many reasons why the information may be incorrect. These reasons could be that the informant simply doesn’t know, or they are deliberately providing information that is incorrect to create the appearance of legitimacy or to meet societal norms.

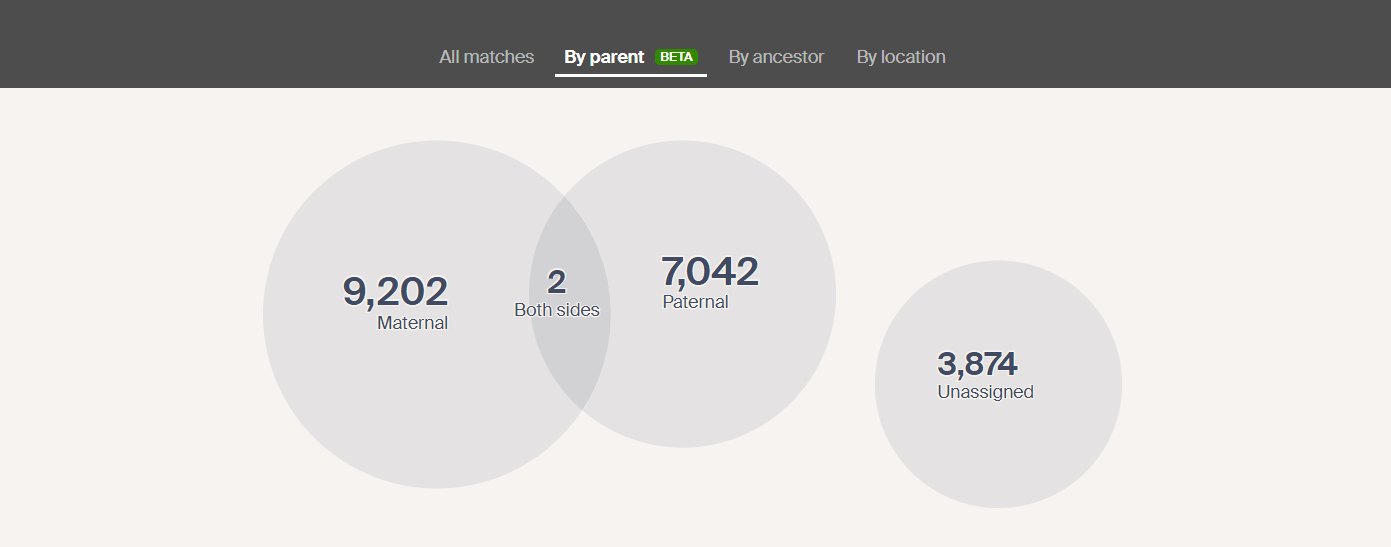

The Family Search website discusses how genealogists can break through brick walls using DNA. DNA matches can help prove relationships and therefore connections on the family tree. To solve a brick wall, traditional research is used to hypothesize a potential relationship. This includes using official records such as births, deaths, marriages, with evidence from cemeteries, newspapers, land titles and other government documents. If a high enough percentage of the descendants share the predicted amount of DNA, a brick wall may be solved.

DNA matches assist in confirming the tree is correct and provides another layer of proof to confirm the branch is correct. For example, my 3x great-grandfather, William Fox had two children with my 3x great-grandmother Margaret Wogan, however there is no evidence they ever married. Before he met Margaret, records show a William Fox married Mary McGrath, and they had four children. There were many males in the colony at the time by the name of William Fox so is he the correct William Fox?

Evidence is required to link William Fox to his two relationships to confirm he is the same person. The evidence available came from the birth certificates of his children. They all show consistent details that William was born in Dublin around 1812. William and Mary’s marriage record has no helpful information. We know they resided in the gold fields near Young before her death. This is confirmed in newspaper reports and birth records. After Mary’s death, William and Margaret’s first child Eliza was born in Hovells Creek, another gold field, 80klms from Young. It was not unusual for families to move from gold field to gold field as discoveries were made but could this be another William Fox from Dublin who made his way to the area to make his fortune?

Confirming they are the same William Fox was assisted by DNA. Matches appeared on my Ancestry account who were descended from William Fox through three of the children of his first wife. We shared DNA of around 25 centimorgans, indicating a 4th – 6th cousin relationship which fits with the relationship we have on the family tree. This was able to prove the connection and the theory William Fox was the same person as theorised through the records.

Another issue is whether Bridget, the second child of William and Margaret, was fathered by William. William disappeared a few years after Bridget’s birth then Margaret married Martin Gill. William registered the birth so it is likely he is the father but to be certain I can check my matches. I went through my list of matches with Bridget’s descendants and found a fourth cousin with shared matches with the cousins descended from Williams first marriage. We all share a piece of DNA from William. He is the father of Eliza and Bridget.

A DNA match received from DNA testing and the shared matches, along with official records and documents, can assist to confirm a theory and prove a connection.