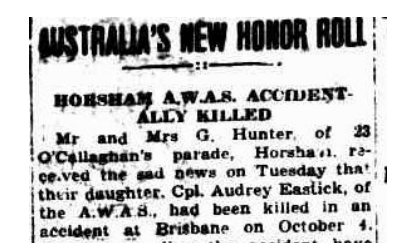

Creating a family tree starts with the date of a birth, death or a marriage but delving deeper into details of a life can uncover secrets and experiences not even a close member of the family may know about. Stories can be pieced together from records from genealogy sites but searching beyond these sites both online and offline

My great-grandfather, James Whirisky died in 1955, well before I was born. When I was older my mum and her sister’s stories of him were of a distant, cranky man who resorted often to alcohol. There were no happy memories or cheerful stories of trips to the pictures or days at the beach. I carried this perception of him into my adult life until the tools became available to fill in the blanks through research.

James Whirisky was born in Dumbarton, Scotland on 9 February 1880 to John and Jane Whirisky, nee Haggerty. John Whirisky was an Ironstone miner of Irish descent. They had a daughter, Jane, in 1881 and then no further children. James and Jane’s mother died in 1884 when James was four years old, and it is unknown who looked after James and Jane after her death. In 1901 John Whirisky appeared on the Scottish census as a labourer and boarder, his children no longer with him.

By 1907 James Whirisky emigrated to Australia to live in Sydney, his sister Jane followed with her husband and two children a few years later. On 25 September 1907, James Whirisky was appointed as a probationary constable with the New South Wales police force, a career he stayed with his entire working life. A year after his appointment, on 21 October 1908, James marrieds Annie Hanson, daughter of a Norwegian waterman and Irish mother, who were both deceased. Annie was living in Paddington and James at Central Police Barracks. She was 24 and James, 28. During her life she had experienced poverty and hardship on the streets of Sydney, living amongst the Irish Catholic population.

Soon after his marriage to Annie, James received a black eye whilst on duty. Richard Long was drunk and disorderly and fighting another man on Liverpool Road, Ashfield. A crowd of over 50 people gathered to witness the brawl and James moved in to arrest him and march him towards the police station. The crowd followed and incited Long to resist arrest. Long fought back and the result was a punch to James’ left eye.

In 1922, then a Constable first class, James was assigned to the historic town of Windsor. The family had grown to five. Phyllis was 13, Hilton, 11 and Edna, 10. Windsor was not quiet country life for James. In his first two months on the job, he attended a robbery of railway tickets at Mulgrave Station and a suicide in the river. James pulled out the body of a stranger to the town. Despite an inquest and witnesses seeing him alive days before, the man’s identity remains unknown. In February 1924, the river again claimed a victim, James assisted to recover the body of 13-year-old Madge Farrell, who losts her life during a day swimming with friends.

Ten months later the family move back to Sydney, living in a house in Carlingford. James was posted to Darlinghurst Station. His visits to see friends in Windsor are reported in the local newspaper. An article in 1931, talks of his ‘kind and gentle disposition’ and his popularity amongst the locals. The same article also mentions his daughter Edna was to be married the following week.

On 11 July 1931, Edna Whirisky married Thomas Nolan at St Georges Church, Hurstville . She was 19, he was a 21-year-old police officer. Their marriage was tumultuous, marred with violence and abuse. By 1936, Edna had left her husband and was living with her parents at their home in Daisy Avenue, Hurstville. She found work as a typist.

On 16 December 1935, James was the victim of an accident not related to his work. He was knocked down by a push bike as he walked home from work. He was taken to hospital, suffering from a fracture of the skull, a broken right forearm, and cuts to the face.

During the early years of World War II, Edna told her family she was leaving to work in Victoria. When she returned to Sydney in 1943, her mental health declined to where she was hospitalised. James, now retired, and Annie take her to Sawtell in the hope the sea air and simple life improved her health. In December 1947, Edna returned to Sydney, booking a room at the People’s Palace in Pitt Street. When she was not seen for several days, the door was forced open. She was found dead, lying on the bed. Beside her is a glass containing the remains of a powder and a handwritten note. She was 36. Fifty years later a woman contacted Phyllis, Edna’s sister, and tells her she is the daughter of Edna Whirisky.

In her later years, James’ wife, Annie lived with her daughter Phyllis in a Sydney unit. She spent her days in a chair by the lounge window, dressed in a housecoat, holding a small transistor radio. Close by is the form guide. I don’t remember her saying a word to me or my sister when we visited, but we had to approach her and kiss her cold, sagging cheek. She died, aged 97, in 1981, taking her family’s secrets with her.

As a couple and a family, James and Annie experienced trauma and stress no family should bear. When I look at the photo I have of them they seem stoic, bravely putting on a veneer of strength, despite what life dealt them. The records can help unearth the experiences a person may not tell anyone in their life and help develop an understanding of who they were as a person, not just a list of dates.