Christmas is a great time to have a conversation with family members about family history. Chatting about family stories with older family members while gathered is an important element to gathering clues to help piece together an ancestor’s life.

My grandfather Frederick James Peeling was born in Shepherds Bush, London on 19 May 1908, to William Peeling and Minnie Legee. He was the second of three sons. When Minnie died in 1915, William married Gertrude Annie Moore and they had one daughter, Phyllis Peeling.

Life became difficult for Fred in the new family unit and by 1924, at age 16, Fred was working in farming, a long way from London, in South Gosforth. The lady he was working for told him about an opportunity of free passage and a job in Australia and he left on the SS Borda on 4 September 1924.

Fred’s brother William had left a year earlier, but his family didn’t know where he was and there were assumptions he had gone to America. I wrote about finding William in Pittsworth in Queensland in a previous blog.

On arrival, they assigned Fred to the Reynolds family farm Dilwyn, named after George and his wife Emily’s English home. It was in Pappinbarra, near Wauchope, on the mid-north coast of New South Wales. The climate and surroundings differed from England, with eucalyptus trees replacing green rolling hills.

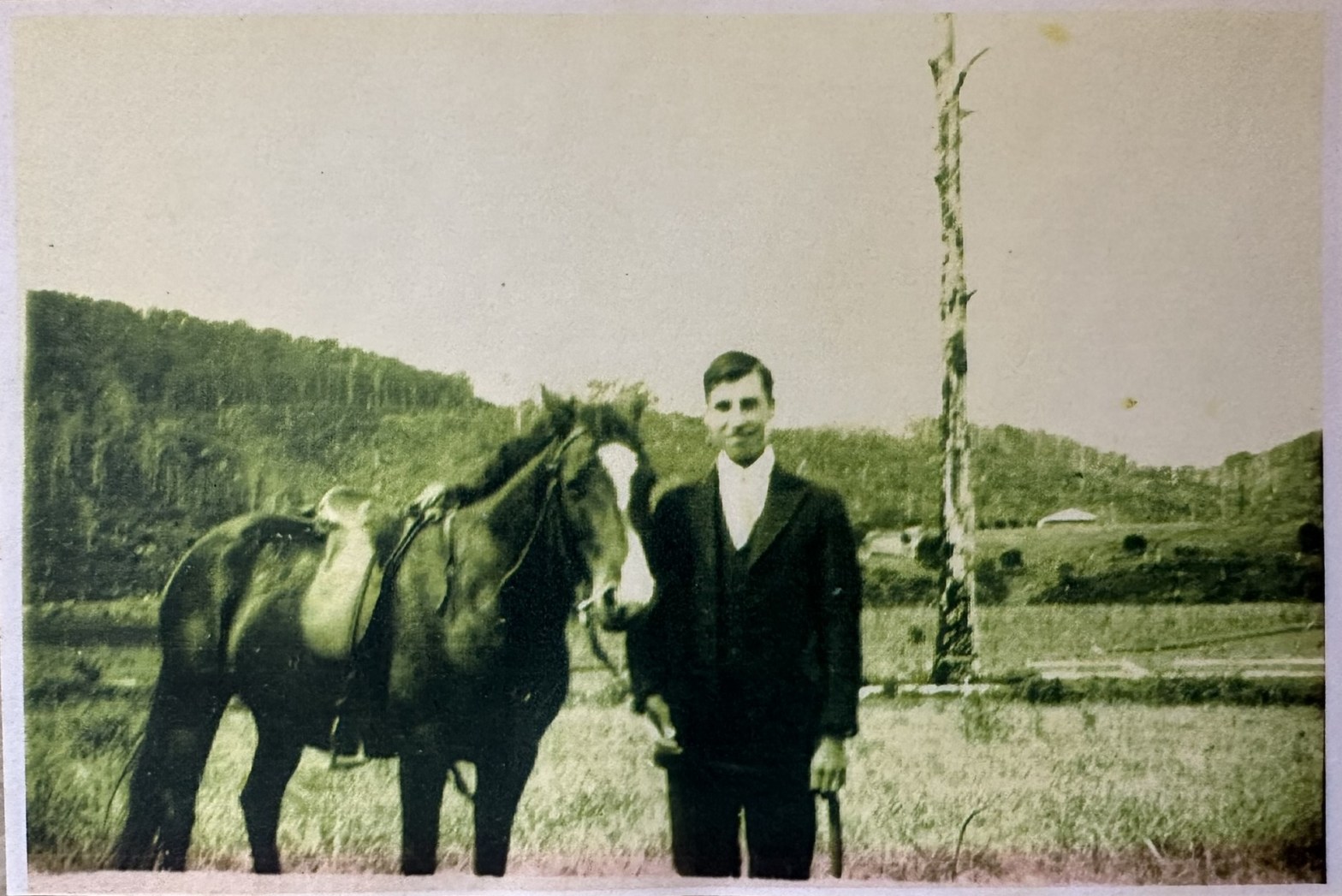

George and Emily had four boys, their eldest George had died in France in 1918 while serving his country in World War 1. George snr had the mail contract between Beechwood and Pappinbarra and the farm ran dairy cows. Fred is in photos, working in long pants and long-sleeved shirts, looking happy and tanned.

In 1931, George Reynolds died, and this event brought Fred’s employment to an end. He moved to Sydney, lived in Hurstville, gained employment with NSW railways, and married my grandmother, Phyllis Whirisky, in 1935.

I was told my grandfather came to Australia, and worked on a farm near Wauchope in a small place called Pattinburra with a family named Reynolds. I couldn’t find a place called Pattinburra but found Pappinbarra by scouting places on the map close to Wauchope and I found details of the Reynolds family from there.

The story developed using births, deaths and marriages indexed in Australia and England, newspapers on Trove, Electoral rolls and emigration records on Ancestry, military records on the National Archives of Australia.

My family believed for along time Fred arrived in Australia under the Dreadnought agricultural labourers’ immigration scheme. Records of the boys who arrived under the scheme are available at several libraries and I viewed the microfilm at the State Library of Queensland. The list of immigrants did not include Fred Peeling and I confirmed this on a visit to the Alstonville, which holds the records collected by the Dreadnought Association. If you have a Dreadnought boy in the family I recommend contacting the Alstonville museum to see what they know of your ancestor. They are very helpful.

Have a wonderful Christmas with your family and don’t forget to ask about those family stories.