Alstonville is a lovely town on the way to Lismore from Ballina on the northern rivers area of New South Wales. As with most towns along the north coast, the settlers were attracted by the plentiful supply of red cedar, a sought after timber for the colony and the export industry.

Land was selected in 1865 and the town grew due to the needs of the expanding population. The cemetery was opened around 1890 and it is on a hill across the current highway from the turnoff to the town. It is a quiet, peaceful setting of well cared for gardens and tropical plants and is still used for burials today.

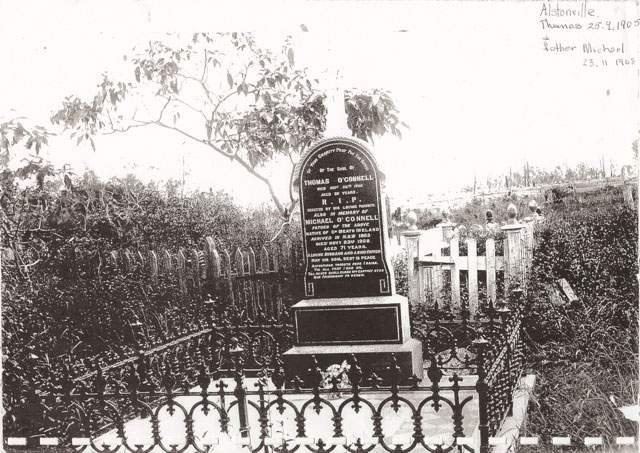

A large black marble monument stands in the Roman Catholic section as a tribute to the O’Connell family. It no longer has the ironwork fence but the marble is in good condition and a tribute to Michael O’Connell, his wife Mary and their son Thomas. Michael and Mary were natives of County Meath, Ireland.

Michael and Mary made the journey to Australia as unassisted immigrants, paying for the full cost of their passage. They departed Plymouth, England aboard the ship ‘Hotspur’, arriving in Sydney on 5 Dec 1863 with 440 other passengers. They first settled at Jamberoo on the south coast of New South Wales where Michael was a farmer. Their first four children were born there.

In about 1870, the family sailed to Ballina and relocated to Duck Mountain, the name given to the area now known as Alstonville. Here they had a further six children. Along with other settlers, the O’Connell family engaged in the dairy industry on the fertile rolling hills. Michael also planted sugar cane. Many small mills operated in the district before larger steam mills were constructed in 1882. By 1896 the Rous Mill boasted a light rail line to transport cane to Alstonville.

Three years prior to the death of Michael in 1908 at age 67, their eldest son Thomas died from consumption, also known as tuberculosis, at age 39. He left a wife and five children, the youngest six months old. It is said in his obituary that Michael never recovered from his son’s death. His funeral was conducted in the Roman Catholic chapel in Alstonville, officiated by the Rev. Father Williams. His coffin was then taken to the cemetery with a very large procession of friends and family following. Father Williams read the funeral service at his graveside and spoke of his impressive life and character and how he, and his sons, had assisted in clearing the land for the church in Alstonville.

Michael was buried alongside his son Thomas. His wife Mary passed away on 26 September 1925 and was buried with her husband and son.