Breaking Through the Brick Wall in Family History Research

Every family historian encounters it eventually: the brick wall. One moment you’re confidently moving backward through generations, names and dates lining up neatly, and the next—everything stops. Records disappear. Names change. A person seems to materialise from nowhere and vanish just as mysteriously. It can be frustrating, especially when you’ve invested hours, months, or even years into your research.

A brick wall often forms for very human reasons. Our ancestors migrated, changed surnames, lied about their ages, avoided authorities, or simply lived in times and places where records were poorly kept or later destroyed. Wars, fires, floods, and administrative neglect have erased countless lives from official documentation. When this happens, it’s not a failure of your research skills—it’s a reflection of history itself.

The first step in breaking through a brick wall is to pause and reassess. When progress stalls, it’s tempting to push harder in the same direction, but that often leads to circular research and repeated dead ends. Instead, step back and review what you know to be true. Separate proven facts from assumptions. Ask yourself where each piece of information came from and how reliable it is. Many brick walls are built on a single unexamined assumption.

Read over all the documents you have. It is amazing what can be missed when you are not looking for it. Analyse every piece of information it gives you. The names on obituaries or witnesses to an event, an informant: they are all important pieces of information that can lead you further. If you haven’t already purchased full transcripts of documents then I suggest obtaining them. Relying on hints in a subscription platform and not reaching further to official indexes can limit the information you obtain.

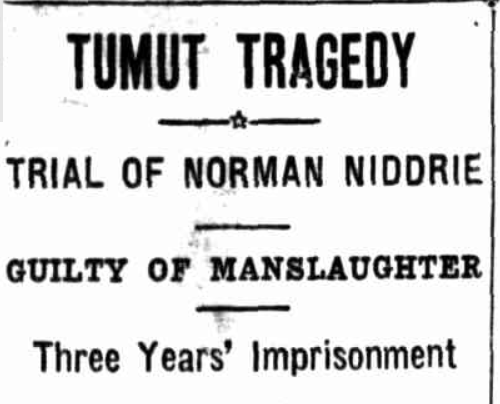

Next, widen your lens. If direct records are missing, look sideways. Research siblings, neighbours, witnesses, employers, and associates. Families rarely lived in isolation, and indirect evidence can be surprisingly powerful. A land record, newspaper notice, court file, or church register may mention your ancestor in passing even when a birth or marriage record does not exist.

It’s also important to remember that spelling was fluid and identities were flexible. Names were written phonetically, altered for convenience, or deliberately changed to fit in or start anew. Try searching with creative variations, initials only, or even first names without surnames. Consider how accents, literacy levels, and record-keepers might have influenced what was written down.

Use your DNA and follow your shared matches. Your DNA results are a second family tree and can support the tree you have or give you new clues. It is the type of jigsaw puzzle that provides unexpected rewards and crack a brick wall.

Brick walls can also be emotional. Family history is personal, and when answers don’t come easily, disappointment can creep in. This is where patience becomes part of the research process. Sometimes new records are digitised, DNA matches emerge, or fresh perspectives appear—but only if you give yourself time and space to return later with new eyes.

Finally, remember that breaking through a brick wall doesn’t always mean smashing it completely. Sometimes the breakthrough is learning why the wall exists and accepting that not every question will be answered fully. Even then, you gain something valuable: context, resilience, and a deeper appreciation for the complexity of real lives.

In family history, brick walls are not the end of the story. They are invitations to think differently, research more creatively, and honour the fact that our ancestors lived lives far richer and messier than any record can capture.